The Atlantic Wild Horse Trail

The wild horses of Currituck Banks:

Corolla, NC

Free-roaming horses have inhabited the North Carolina Outer Banks for centuries. At one time, they numbered in the thousands, ranging over the 175-mile (282-km) span of islands from Shackleford Banks north into Virginia. As recently as 1926, an article in National Geographic stated that there were between 5,000 and 6,000 horses roaming the Outer Banks (Chater, 1926). They grazed in the marshes, drifting out to the beach in the hot summer months to escape biting insects and catch the sea breeze. Like the human residents of the Outer Banks, these horses were rugged, tenacious, and independent.

On Currituck Banks, the northernmost reach of the Outer Banks, a herd of wild horses has been in residence for centuries. These horses are strikingly Spanish in appearance—short-backed, deep-chested, and wide between the eyes, in shades of black, brown, bay, sorrel, or chestnut. They are strikingly beautiful, and even the hard-hearted cannot help admiring them as they travel along the water’s edge. There is no question that these horses carry the blood of the ancient Spanish Jennets brought to the New World by conquistadors, but just how those bloodlines reached the Banker Horses is a topic of hot dispute. Some think Spanish explorers left horses deliberately on barrier islands in the sixteenth century. Others quote legends in which the original progenitors swam ashore from ancient shipwrecks. Most likely, they are the descendants of Spanish-blooded colonial livestock that English settlers placed on the barrier islands to graze. Early settlers migrated down from the Chesapeake area before 1700 in search of land on which to graze livestock—ideally, that which was unsuitable for any other purpose. The earliest colonial farm animals included Spanish stock bought (or, according to some accounts, stolen) in the West Indies, probably from some of the same ranches that supplied horses to the conquistadors. Marshy lowlands provided good forage and required little investment. Livestock could be contained on a peninsula with only a fence at some narrow spot or on a barrier island with no fence at all. Before long, islands and necks all along the East Coast supported free-range livestock, including Boston Neck; Staten Island, New York; Point Judith, Rhode Island; and many parts of Long Island. The first Georgia colonists likewise turned livestock loose in nearby river swamps and "feeding marshes" as well as on barrier islands. In a ritual hundreds of years old, stockmen held roundups once or twice a year to establish ownership of new calves and foals and to remove animals for use on the mainland. The rest of the year, the animals roamed free, unattended. In 1935, the North Carolina General Assembly passed legislation requiring livestock owners on barrier islands from the Virginia line to Hatteras Inlet to contain their animals within fences. Many of these stockmen did not own large tracts of land and had allowed their animals to graze in marshland owned by neighbors or absentees. In the depths of the Great Depression, stockmen who might have maintained livestock profitably on their own property were reluctant or unable to invest in fencing, dipping vats, and other things required by law. Suddenly families comprising generations of herders were forced to find another livelihood. Within a few years, the number of substantial livestock operations on the Outer Banks shrank from about 50 to seven or eight. The few horses that evaded capture or slaughter retreated to the most remote reaches of the northern Banks, near Corolla, where they peacefully coexisted with the residents. The village of Corolla was originally called Whales Head, then renamed Currituck Beach. When the post office opened around the turn of 20th century, the little town was named Corolla. Until 1973, the only land access was by 15 mi (24 km) of rutty, unpaved state road from the south or by beach from the north. Developers paved a road north to the village, but restricted access until 1984. When the state took over responsibility for maintaining the road, the outside world descended on the little village. Before 1986, there were only 35 full-time residents. A decade later that number had more than tripled, but the bulk of the population influx came from thousands of people eager to rent seasonal beach homes or just visit for the day. The dark horses that often crossed the road at night frequently had fatal encounters with the impatient drivers that flew down the new roadways. By 1989, 17 horses had been killed in road accidents—six of them in a single incident. Corolla residents and visitors united to create the Corolla Wild Horse Fund. Their mission was to guard the Corolla horses against the human invasion and attempt to preserve their wildness. The horses needed government protection, but because most government agencies consider them non-native wildlife, they were ineligible. Hunt clubs complained that they ate the food planted for the waterfowl and asked the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission to remove the herd; but the agency refused because horses were not considered native wildlife and were therefore not its concern. Currituck County looked to the state for help. The state bounced the responsibility back to the county. As Corolla residents wrestled with red tape, horses were dying on the highway. The Corolla Wild Horse Fund outfitted the horses with reflective collars to make them more visible to motorists, sprayed their bodies with glow-in-the-dark paint, and posted signs along Highway 12 warning motorists to slow down because of “horses on road at any time.” These tactics helped to reduce, but not eliminate fatalities. Some signs were even stolen by vacationers for souvenirs. The horses were not afraid of people, so visitors assumed that they were tame. They fed them junk food, patted then, and even placed children on the backs of these untrained 700-pound (300-kg) animals. People were injured by contact with horses, horses were injured by contact with people. Eventually, the horses were recognized as a cultural resource worthy of protection. In 1997, Currituck County officials assembled members of the Wild Horse Fund, the Currituck National Wildlife Refuge, and the North Carolina National Estuarine Research Reserve to work out a management plan which has since been updated. The 13-point plan allowed only 60 wild horses can remain on Currituck Banks, an arbitrary, unscientific number. “That is not a viable number, particularly for a population that has already had a great erosion of genetic variability,” said Dr. E. Gus Cothran, equine geneticist. Moreover, a small herd is easily destroyed by disease, drought, fire, flood, or hurricane. This risk is very real. On Cumberland Island National Seashore, a 1990 outbreak of mosquito-borne eastern equine encephalitis killed 40 horses. In the Assateague herd, Kirkpatrick (1994) writes that during the summers of 1989 and 1990, nearly 40 of the Maryland Assateague Ponies died of EEE, and 12 drowned in a single storm. The Corolla Wild Horse Fund built a fence with donated money, land, materials, and labor, hoping to encourage the horses to stay within the largely uninhabited, unpaved area of northern Currituck Banks. The horses were unimpressed and simply walked around the ends of the fence to resume grazing on the green lawns of Corolla. In 1995 an improved sea-to-sound barrier was completed, this one reaching well out into the water to keep the horses north of town. It took two days to herd the horses north of the fence, where they joined other bands that ranged as far north as Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge. The Corolla Wild Horse Fund built a second sea-to-sound fence 11 mi (18 km) north of the Corolla barrier along the southern border of False Cape State Park at the Virginia line. Horses sometimes find their way through, around, or over this fence to range into the Back Bay NWR and even into the Sandbridge neighborhood of Virginia Beach. The fence keeps the horses out of the paved and thickly settled village of Corolla, but the same problems continue. Horses are still being hit by vehicles and left to die slowly, only now the horses are in danger from 4x4s and ATVs on the beach. Three horses were struck by vehicles in 2009. In her first four years as director of the Corolla Wild Horse Fund, Karen McCalpin experienced the deaths of 19 horses, most of them accidental and caused by humans. Unintentional killings are heartbreaking enough, but, incomprehensibly, there have also been premeditated shootings. Between 2001 and 2007, seven horses were gunned down in cold blood and left to decompose. The shooters are still at large despite a $12,550 reward for information leading to their arrest. Horse breeds are always changing, and there is always a balance to be struck between keeping bloodlines pure and losing genetic diversity. Too much diversity, and uniqueness of the population is lost; too little, and the population will collapse. In the early 1990s the Currituck herd had fewer than 20 individuals. As a result of this genetic bottleneck, genes were irretrievably lost. In 2009, there were only about 100 breeding mares in the Currituck and Shackleford herds combined. Upon taking the CWHF Executive Director position in, Karen McCalpin recognized that if the herd was managed at 60 animals, there would eventually be a complete genetic collapse similar to that experienced by the Ocracoke herd. Dr. E. Gus Cothran evaluated the genetic makeup of the Corolla herd in 2007 and found that its genetic diversity is among the lowest that has ever been found in a horse breed. Low genetic diversity and low numbers are the two greatest threats to the Corolla herd. In a small, closely related population like the horses of Currituck Banks, diversity is more important than numbers alone if they are to survive for the long haul. The Corolla herd descends from a single maternal line. The herd members are closely related, and as a result each generation is seeing an increased incidence of heritable defects such as locked patellas, contracted tendons, and parrot mouth. By contrast, the Shackleford Banks horses are genetically healthy, with three maternal lines. A herd of 60 genetically diverse horses is more likely to to thwart the specter of extinction than a herd of 150 inbred animals. When introduced into a failing herd, a single stallion has the potential to impregnate many mares simultaneously and shift the herd genome toward better health more rapidly than a mare, which almost never carries more than one foal at a time. But for stallions, reproductive success is far from certain. Before he gets a chance to breed, a mature male must fight seasoned stallions to win mares and retain them in his harem. Many young stallions do not have the skills to entice mares and fight or bluff to keep them. In July 2014, McCalpin and Cothran collected DNA samples from horses in the Cedar Island, N.C., herd via dart gun to evaluate possible candidates for genetic exchange. Although there have been horses on Cedar Island for more than 100 years, many in the current population were translocated from Shackleford Banks after most of the original herd was euthanized for carrying equine infectious anemia. Both the Corolla and Shackleford/Cedar herds appear to have descended from the same original population, and mating between the two groups would not be considered crossbreeding. Cothran analyzed the DNA of the two most promising prospects, then rejected a gorgeous silver dapple colt because he carried the gene for ocular anomalies. Ultimately, on November 20, 2014, the Corolla Wild Horse Fund introduced a stallion "Gus" from the Cedar Island herd. Named for Gus Cothran, who was instrumental in this revitalization project, the stallion will breathe new life into a dying gene pool if he successfully mates with Corolla mares. By 2020, he had yet to produce a single foal. A highly polarized battle wages between those who want the free-roaming horses removed as destructive and damaging, and those who want them to remain as desirable and beneficial. Both sides can cite abundant research to support their viewpoints. Detrimental or potentially detrimental effects of free-roaming herbivores have been documented by numerous papers and studies, including Barber & Pilkey , 2001; De Stoppelaire et al., 2004; Oduor, Gómez, & Strauss 2010; Seliskar, 2003; Turner, 1987, Nimmo and Miller 2007). Alleged damage includes soil loss, compaction, and erosion, trampling of vegetation, reducing abundance of plant species, birds, and fishes, killing native trees through bark chewing, damage to bog habitat and water bodies, promoting weed invasion, altering community composition of birds, decreasing nesting habitat for gulls and terns, fish, crabs, small mammals, reptiles, and ants, and reducing plant biomass and salt marsh vegetation. Conversely, many researchers have demonstrated the beneficial or potentially beneficial effects of the grazing of large herbivores on ecosystems, especially wetlands and grasslands (Keiper, 1981; Stahlheber& D’Antonio, 2013, Anderson, 1993; Benot, Bonis, Rossignol, & Mony, 2011; Duncan & D'Herbes, 1982; Levin, Ellis, Petrik, & Hay, 2002; Menard, Duncan, Fleurance, Georges, & Lila, 2002; Plassmann, Laurence, Jones, & Gareth Edwards, 2010; Stroh, Mountford, & Owen, 2012; Vavra, 2005; Wylie, 2012). Documented beneficial environmental effects of feral horses include

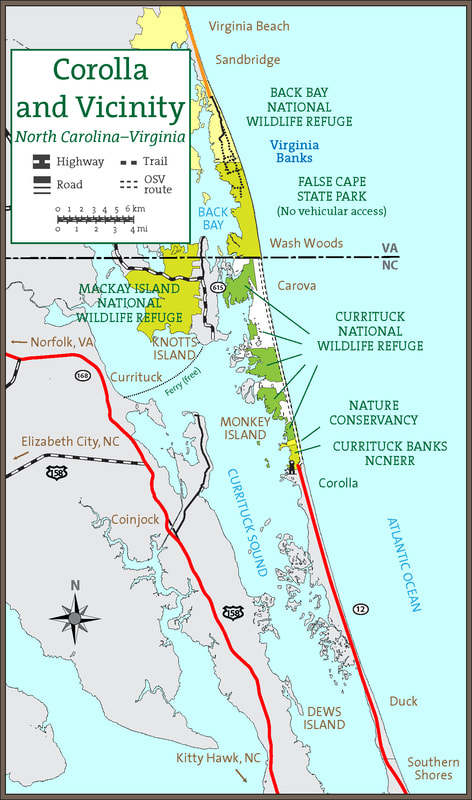

The Currituck herd ranges on about 7,544.25 acres of the north beach, none of it a wild horse sanctuary. About 70% of their range is privately owned, and the other 30% is public land specifically set aside for “native” wildlife preservation. The agencies managing the federal land view feral horses as competitive with indigenous species for habitat. In December, 2013, the Currituck NWR erected 3 miles (4.8 km) of dangerous barbed wire fence, excluding the horses from their property and putting them, other animals, and people at risk of horrific injury. Despite public outcry and political pressure, the fence remains. The development boom continues on Currituck Banks, and a proposed bridge to connect Corolla directly to the North Carolina mainland will encourage more visitors. The northern parts of Currituck Banks are becoming more appealing to developers. As of 2010, there were 3,090 platted lots and more than 1,300 existing homes, including mansions with more than 20 bedrooms. The Currituck herd represents one of the rarest strains of Colonial Spanish Horses. For centuries, they have bred almost entirely to one another, and over time they became a unique population and one of the oldest surviving American breeds. Conant, Juras, and Cothran, writing about the Colonial Spanish horses of the southeast, commented that “these relic populations are worth preserving, both for their genetic as well as their historical heritage as descendants of the first modern horses in the Americas.” Other strains of Colonial Spanish horse include the Belsky, the Cerbat, the Choctaw, the Florida Cracker, the Marsh Tacky, the New Mexico, the Pryor Mountain, the Santa Cruz, the Sulphur, and the Wilbur-Cruce. All of these breeds are exceptionally rare, both collectively and individually, with a total global population of less than 2,000. A Web site that receives more than 1 million hits annually serves as an information hub at http://www.corollawildhorses.com and includes a lively, poignant blog to keep enthusiasts up to date with the herd happenings. These animals owe their liberty to the advocates who have battled so relentlessly on their behalf. With continued providence and careful protection, these beautiful animals can continue to run on the Carolina coast in the centuries ahead, but maintaining a viable herd will require deliberate conservation efforts. Says Steve Edwards of Mill Swamp Indian Horses in Smithfield, VA “Extinction lasts forever and the clock is ticking.” Bonnie Gruenberg 2015 Respect free-roaming horses as wildlife. Keep at least the length of a large bus between you and the horses at all times, and try not to disrupt their behavior with your presence.

|

Learn More!

Books by Bonnie Gruenberg

Respect free-roaming horses as wildlife. Keep at least the length of a large bus between you and the horses at all times, and try not to disrupt their behavior with your presence.

Corolla Horses Links

|

|

How we DID that...

© Bonnie Gruenberg 2021 Synclitic Media LLC Schoolhouse Rd New Providence, PA 17560 [email protected] (717) 723-8341 |

|