|

The Atlantic Wild Horse Trail

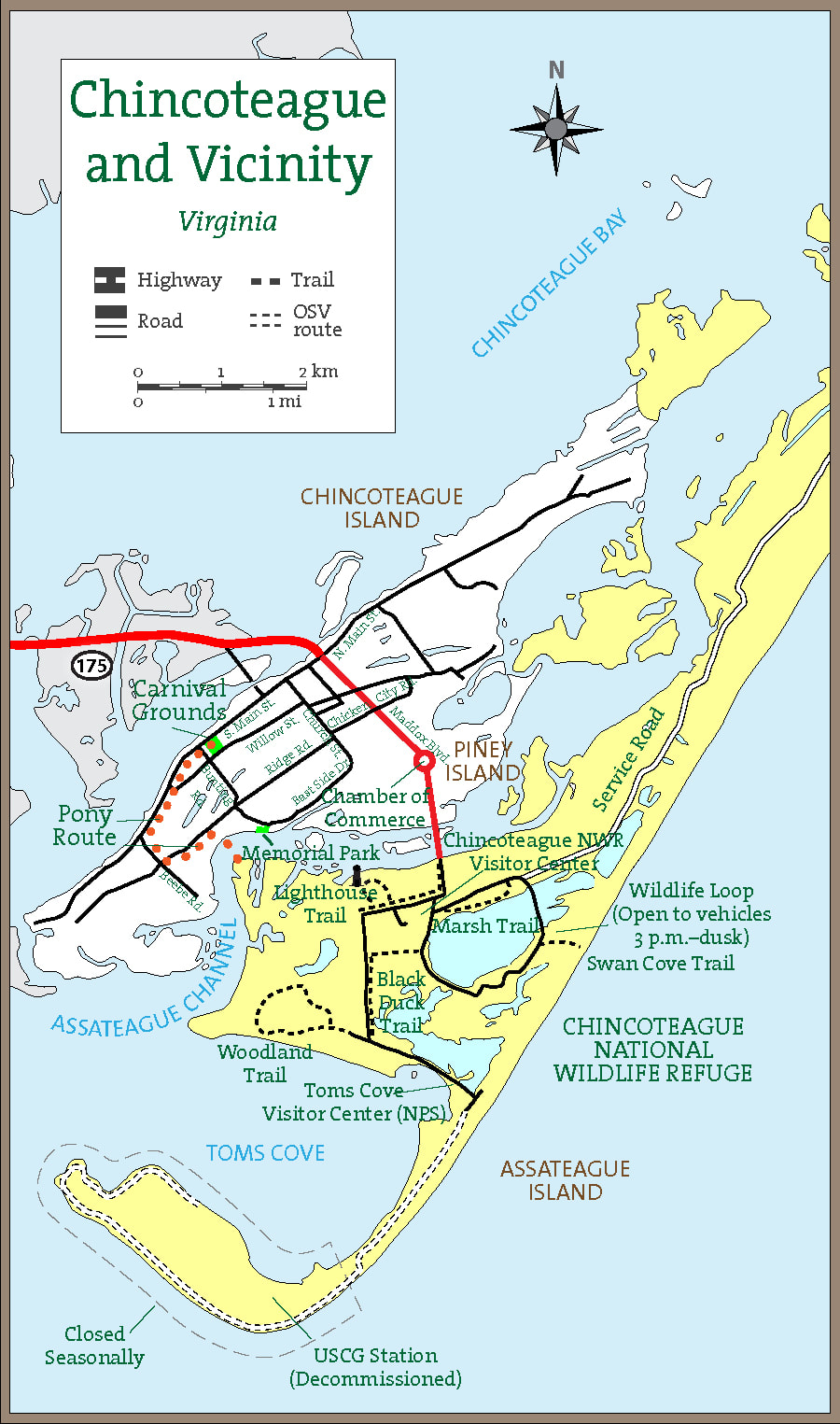

The wild ponies of Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge on Assateague Island, VA Chincoteague is a small island community on the Eastern Shore of Virginia that historically made its living from the sea. Already world-famous for its oysters, Chincoteague saw increased recognition and tourism in 1947 with the publication of Marguerite Henry’s book, Misty of Chincoteague. Although there are festivals and activities held in Chincoteague year-round, the biggest draw is the wild ponies that live across the bay on Assateague Island in the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. The climax event is the July Pony Swim, which attracts crowds of tens of thousands and is covered on national television. Many locals believe that the original horses swam to shore from the wreckage of sixteenth century Spanish galleons. Historians and biologists believe that the majority of ponies are probably descended from domestic stock put there to graze in the late 1600s. This stock was frequently Spanish in origin, because early colonists bought their livestock from the same Spanish ranches in the Caribbean. Whether hey arrived by shipwreck or by colonists, the horses would have originated from the Hispaniola breeding ranches either way. The first account of pony penning on Assateague was published in 1835, and the practice was traditional and long-established by then. Toward the end of summer, local men would participate in the capture, branding, and sale of the ponies, an event that developed into a major celebration that drew crowds and spawned parties. These ponies were solid-colored—bays, blacks, and sorrels. They sported thick, often curly manes and tails that spoke of their Spanish ancestry. Anyone who purchased marsh land was allowed to lay claim to any ponies living on it. The peak of human settlement on Assateague reached 225 individuals around 1900. During the 1920s, one man, Samuel Field, owned much of the Virginia end of Assateague and would not allow others in the community access to the seafood beds of Toms Cove. The residents simply floated their homes across the bay on barges and set up residence across the water on the island of Chincoteague. With so much of the land privately owned, pony penning became difficult. The locals established a single penning for both islands, held on Chincoteague. Initially, the ponies were ferried across from Assateague by boat, but in 1925 they were swum across the channel, as is done today. Since the 1920s, thousands of visitors have packed the island every July to witness the pony roundup and sale. Saltwater Cowboys mounted on their own full-sized horses gather the north and south herds and corral them off Beach Road on Assateague. On the last Wednesday of the month, the Cowboys drive the lively, cavorting ponies into the water, where they swim the channel to Chincoteague. They emerge looking pleased with themselves and rest for a short time before the Cowboys herd them down Main Street to the holding pens at the fairground. The fire department auctions the spring foals and a few yearlings, but very young foals are allowed to remain with their mothers until fall. Each year certain foals, usually fillies, are designated buy-backs. Buy-back foals are sold at auction to charitable individuals or groups who donate them back to the fire company for re-release on Assateague as breeding stock. Until the 1920s, Chincoteague was a fishing village accessible only by boat, with schools, a post office, and many homes, mostly made of wood. The streets were narrow, and the houses were built close together. When a building was destroyed by fire early in the 1900's, people realized that they needed to purchase fire fighting equipment and train a team how to use it. They bought a hand pump engine, and later a gasoline engine. But when a serious fire struck fifteen years later, the neglected equipment malfunctioned. Twelve homes and businesses were lost. Four years later, another fire took most of the buildings on the west side of the island. Chincoteague residents vowed that this preventable tragedy would never recur. In May, 1924, the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company was born. To raise money for fire equipment, the annual Firemen’s carnival was organized, which included the roundup and auction of the Assateague ponies. Revenue from annual carnivals and auctions allowed the fire company to keep pace with the requirements of a growing population. In the early 1900s, the development of wetlands and the black market for waterfowl and their feathers pushed many native species to the brink of extinction. The Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1943 as a breeding and wintering area for migratory and resident waterfowl on the Virginia portion of Assateague. The refuge protected about 9,000 acres of coastal wetlands and wildlife. The land in question, however had been free-range grazing land for hundreds of years, and locals petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to continue this generations-old practice. A special use permit was granted to maintain the historic pony herd. The Fish and Wildlife Service removed the cattle, sheep and hogs that free ranged over the whole of Assateague. They erected fences to restrict the ponies to a small pasture comprising only 5 percent of the refuge. Almost all of this land was salt marsh, which provided abundant food, but no way to escape the torment of insects, and no high ground to climb in storms. When the Ash Wednesday Storm of 1962 flooded the Assateague lowlands, 22 ponies in the refuge drowned (as well as about 100 on Chincoteague). In 1965, the fences were reconfigured to give the ponies access to high ground and to let them range more freely. They are currently kept in two compartments, designated as the north and south pastures. In 1947, Marguerite Henry published the best-selling book Misty of Chincoteague, which became a successful movie in 1961. This fictionalized account of the Assateague ponies and the adventures of two Chincoteague children remains popular today and contributes to tourist traffic on Chincoteague. Misty was a real pony born on the Beebe ranch—not on Assateague, as in the book. Henry fell in love with the week-old Misty while visiting Chincoteague, and bought her. Paul and Maureen Beebe, who inspired the characters by the same name in the book, halter-broke and gentled the pony during her stay on their ranch. When Misty was weaned, Henry had her shipped out to her home in Illinois to provide inspiration while she wrote her famous story. While the story line of Misty is not factual, the setting is true to life, and Henry presents a fairly accurate portrayal of pony penning around the 1940s. Over the years, the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company has increased the genetic diversity of the herd by purchasing ponies that were true to the original bloodlines from local owners and by introducing outside horses. Historic accounts indicate that until the early 20th century, Assateague ponies were mostly chestnut, bay, brown, or black and showed conformation very similar to the North Carolina barrier island herds. Rugged Shetland ponies were introduced to the herd in the 1920s to give the ponies flashy pinto coloring. Bob Evans, an Ohio restaurateur, donated two buckskin Spanish Barb stallions. In 1939, the fire company brought in twenty mustangs from the West, and in 1978 added forty more. The addition of the forty mustangs in 1978 was in response to an outbreak of Equine Infectious Anemia that had reduced the herd substantially. In 1975, half the herd tested positive, and affected individuals were destroyed three years later to halt the spread of the disease. Mustangs were brought in from the West to revitalize the gene pool and rebuild the population. But as hardy as these mustangs were, many could not adapt to barrier island life and died within the first year. The famed stallion Surfer Dude and his son Riptide descend from Broken Jaw, one of these Western mustangs. The fire company gathers the ponies three times a year for vaccinations, worming, veterinary inspection, and farrier attention. The fire company provides watering troughs and supplies hay to help the ponies though a difficult winter. If a horse is injured, the firefighters bring the horse in off the range and doctor its injuries. The animals breed at will, but foals are sold at auction each July, the proceeds benefitting the fire company. Assateague Island is fortunate to have escaped the clutches of civilization, although man has left his mark in many places. The Wildlife Refuge is easily accessible to visitors. Many come to see wild ponies, but birdwatching is also popular, especially during spring and fall migrations. Massive flocks of snow geese make their dramatic entrance in November. The lighthouse is open for climbing (but has been closed during the pandemic) and there are excellent hiking and biking trails. The ponies are numerous, not at all shy of visitors, and easily viewed from an observation platform or fences along the roadside. Barbed wire keeps them off the pavement and away from people. Separation is safer for both ponies and visitors, but can make it difficult to view them at close range. When they are on the refuge, good photographs usually require a telephoto lens. The Chincoteague Natural History Association offers educational bus tours, led by knowledgeable guides, to parts of the refuge that are otherwise only open to pedestrians. You will almost always see ponies, often at close range, as well as waterfowl and other wildlife. Additionally, numerous boat tours take visitors to Assateague and afford close-up views of ponies and other wildlife. While Chincoteague watermen still ply their trades in the nearby ocean and estuaries, this seven-mile-long island is covered with tourist-driven businesses and remains lively with visitors though most of the year. Whether you are visiting to relax on the beach or enjoy the little shops, Chincoteague is a world apart. Respect free-roaming horses as wildlife. Keep at least the length of a large bus between you and the horses at all times., And try not to disrupt their behavior with your presence.

|

Chincoteague Links

|