The Atlantic Wild Horse Trail

The wild horses of Assateague Island

National Seashore, Maryland

|

The wild horses of Assateague Island National Seashore are bold. Too bold. They brazenly wander into the campsites in search of good grazing and any tidbits that they can beg from obliging humans. They walk under clotheslines and step on beach towels. They sniff and sometimes sample food cooking inches from open fires, and excavate scraps from the cooling coals. Itchy foals view most human contraptions as potential scratching posts, from barbecue grills to truck bumpers. They tear large holes in screen houses and walk on in, even if there is nothing inside. Campers shoo them away with the loud clanging of a spoon against a pot. It does not frighten them, but signals the animals that they are not welcome and should take their activities elsewhere.

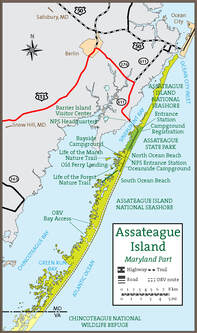

Many visitors cannot understand that these friendly, curious animals pose any threat to them. Although the ponies are largely unafraid of people, they are not tamed or trained. Bites and kicks are commonplace. Often, the perpetrator was a horse who was standing docilely moments before the scene turned ugly. Signs and pamphlets warning of danger do not stop naïve visitors from seeking close contact with them. Some feed the horses from their cars and, in effect, train them to stand in the road waiting for handouts. Horses are killed by drivers who did not expect to see them on the pavement. Additionally, rangers impose fines of $175 per incident upon visitors caught feeding, petting, or approaching within 10 feet of horses or other wildlife. Some believe that the original Assateague horses swam to shore from the wreck of a Spanish galleon, but there is no clear evidence to support this theory. Most likely, free-range horses were deliberately introduced by the colonists in the late 1600s, a time when colonists routinely used barrier islands along much of the Atlantic Seaboard as a grazing commons for livestock. In 1968, the National Park Service took possession of Assateague, acquiring the holdings of landowner Paul Bradley and the 21 ponies that grazed it. These foundation animals—nine stallions and 12 mares—became the nucleus of the Maryland resident herd. All the horses on the Maryland end of the island descend from this population, and no outside horses have been introduced since the National Park Service took over its management. Every organization that manages wild horses must decide how much human intervention is appropriate. Management options run the gamut from keeping hands off, as with the herd at Cumberland Island NS, to providing food, shelter, reproduction assistance, and health care, as with the herd on Ocracoke, North Carolina. With the most intensive management, they are indistinguishable from domestic horses, trading off freedom for better health and security. Managing a herd with minimal intervention allows greater freedom, but greater exposure to disease, parasites, weather extremes, and inbreeding. The National Park Service has targeted a herd size of 80–100 horses for the Maryland portion of Assateague, and manages these animals as as wildlife. Horses have no predators and roam the park as protected and brazen and self-important as the sacred cows in New Delhi. Aside from contraceptive vaccines to limit herd growth, the horses north of the fence live their lives bereft veterinary attention or other human caretaking. Because it manages the horses as wildlife, the Park Service summons a veterinarian only if human activities have caused injury. From the time Assateague first became a national seashore, the horses have been free to live as wild horses, exhibiting natural behavior and subject to natural processes. Ponies can be seen with lacerations, hoof overgrowth, or other injuries or signs of illness. Age takes its toll; elderly horses may develop prominent ribs, sharp spines, and rough coats. When the wild horse population increases beyond the targeted population range, environmental damage can occur, and horses may consume or destroy resources needed by other species, some of them endangered. In 1993 the Park Service began to use porcine zona pellucida (PZP) immuncontraceptive vaccines to decrease the birth rate for horses on the Maryland portion of Assateague. Each mare is given the opportunity to deliver one foal, then is vaccinated against pregnancy for the rest of her life. Unburdened of the demands of repeated pregnancy and lactation, contracepted mares live an average of 9 years longer than mares allowed to reproduce at will. These vaccines have allowed some of the free-roaming horses of Assateague to live beyond the age of 30, which is well beyond the 20 year average lifespan before implementation f the vaccine. Currently, the Assateague herd is genetically healthy, and the Park Service tracks the lineage of individual members. In the future, horses may be added to the Maryland herd if the gene pool shrinks or if disease or disaster devastates the population. These additions would be chosen from other East Coast barrier island populations which are similar to the existing Assateague horses, yet different enough to revitalize the gene pool. Until the early 1900s, Assateague was part of a long peninsula passing through Maryland into Delaware. The Great Hurricane of 1933 opened Ocean City Inlet, and thereafter Assateague has been an island. Littoral currents, produced by waves that hit the beach at an angle, have since attempted to fill it with sand, but dredging and painstakingly maintained jetties maintain the waterway. In the 1930s, Assateague was surveyed as a potential site for a national seashore, but the plan never gained traction. Instead, Assateague started along the path of becoming a developed beachfront community much like Ocean City, MD. In the 1950s, Leon Ackerman and a group of investors bought and surveyed 15 miles of Assateague oceanfront property north of the Virginia line and laid out more than 2,000 residential and commercial lots. Builders erected more than 200 structures, and paved a road, Baltimore Boulevard, to the Virginia state line. They dug deep channels for marinas and for mosquito control. When revenue was insufficient to fund a bridge to the mainland, the developers strategically donated a sizable tract of land to the state of Maryland to create Assateague State Park, and the state funded the Verrazano bridge. Assateague was on its way to becoming another bustling resort city—until the Ash Wednesday storm of 1962. This powerful nor'easter destroyed almost every home on the island. Sheets of seawater literally picked up houses and dumped them in the marsh. Two new inlets cut across the island. Baltimore Blvd. was ripped apart. (Large broken chunks of roadway remain along the "Life of the Dunes" nature trail in the seashore.) After this reality check, developers and home owners alike wondered if perhaps the barrier island was too unstable to support a resort community. Ideas to turn the whole island into a national seashore revived, and the national park took shape in 1965. Today, Assateague Island National Seashore presents a unique opportunity to observe the activities of horses in the wild. The visitor center offers programs, exhibits, and educational materials that familiarize visitors with the resident herd of horses, native species of flora and fauna, and the complexities of the ever-changing barrier island environment. Assateague Island National Seashore is popular park in the summer, lying within a half-day's drive of one fifth of the United States population. Most visitors stay in the developed area, and it is still easy to find empty beach and seclusion if one is willing to hike a short distance. Great beauty is everywhere in all seasons, and the solitude provides opportunities for introspection, renewal, and reconnection with nature. Respect free-roaming horses as wildlife. Keep at least the length of a large bus between you and the horses at all times, and try not to disrupt their behavior with your presence. |

Assateague Links

|